By Laura Sanders

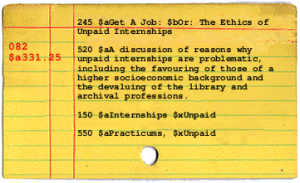

Make your own card catalogues at blyberg.net

Well, it’s that time of year again…classes have wound down, we have (mostly) caught up on sleep after the bleary, stress-filled days of final exams and projects. And now, as we step blinking into the sunlight for the first time in months, our minds turn to the chirping of birds, the roar of road construction…and summer work.

But just as exams and projects are stressful, finding a way to occupy your summer brings its own concerns.

Many library school students will spend their summers doing internships, or as they are more commonly known in Canada, practicums. The School of Information Studies at McGill University, where I attend library school, offers such a summer practicum program. Participants spend ten hours a week during the summer doing unpaid work at a variety of institutions, including public libraries, university libraries, school libraries, hospitals, museums, corporations, and archives. When it was first announced, I was extremely interested in participating, but I soon began to have reservations. In fact, I find the whole idea of practicums/internships extremely problematic.

On the plus side, practicums provide library students with hands-on opportunities that they probably wouldn’t be able to get otherwise. You get a taste of a real working environment, you do a range of different things, and you actually get to apply the concepts you’ve been talking about in class all year. Practicums also provide valuable networking and mentoring opportunities. And since we live in the real world, we have to acknowledge that if organizations were required to pay their practicum students, these positions would not be nearly so plentiful. But as this article in The Atlantic points out, practicums/internships nonetheless have an element of exploitation: “Internships have become an inextricable part of the college experience and a pre-req for post-graduate employment. But this presents a Catch-22 for lower-income students who want to work in politics, research, journalism, non-profits, or other industries that traffic in unpaid internships.”

In short, students who can’t afford to work for free miss out.

Back in February, a mass e-mail was sent to everyone in my program about a summer library internship available with the United Nations in Vienna. I was able to think of several particularly sharp and knowledgeable classmates who would have made excellent candidates for it, and the opportunity could no doubt have launched a stellar career for each of them. But as the internship program does not reimburse students for travel expenses, living arrangements, or visa costs, none of us could afford to do it. By not providing any financial recompense for its interns, the UN is excluding many of the brightest and best in the field in favour of applicants who come from privileged socio-economic backgrounds. Admittedly, this is an extreme example, but I do find it ironic that an organization that spearheads international aid does not facilitate the induction of a more diverse range of people into its ranks.

As blogger named Lance at New Archivist states in this post: “I think most people will agree that diversity includes not only people of different racial and ethic backgrounds, but people of different economic backgrounds and experiences. However, at the same time we are giving a lot of lip service to diversity, we are also constructing roadblocks to achieving those goals.” People from all walks of life have a great deal to contribute to the library and archival communities and should have the opportunities to do so.

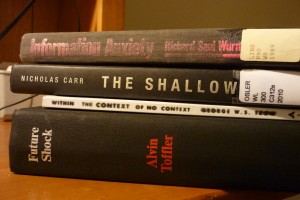

But not only may we be driving away those of lower socio-economic backgrounds, the willingness of volunteers to do the work that requires professional expertise undervalues our profession. This is the exact opposite of what we should be doing. Sadly, this is an age where most people don’t see the relevance of librarians and archivists anymore (including, sadly, the Canadian federal government, which recently made enormous cuts to Library and Archives Canada). The task falls to us to be tireless in our efforts to explain why our services are more necessary than ever.

The summer practicum is not an option for me. At thirty years of age, I am too old for parental assistance and because I was employed full time before starting library school, I am not eligible for student loans. I am funding my studies through a combination of personal savings and part-time work during the school year. Full-time summer employment is my only chance to counter the alarming depletion of my bank account. Of course, because the library field relies so much on student practicums, summer library positions for students are few and far between. I spent much of April grinding my teeth wondering how it would all pan out.

A potential solution, one that The Atlantic doesn’t mention, is government programs. I was hugely fortunate to find full-time summer employment in the library field through a government-subsidized program called Young Canada Works. It provides grants to public institutions such as libraries, museums, and NGOs to hire summer students. The program is hugely beneficial to both parties. The student is paid a fair wage and gains experience in his or her field, and the hiring institution gets a helping hand at no cost to them. At my job I get to do a bit of everything: circulation, cataloguing, home delivery, selection, weeding, and event planning. It will go far toward helping me find a professional position after graduation. I thank my lucky stars that the Canadian government funds this program. As it turns out, my employer has also hired practicum students through McGill’s program, and our job descriptions are basically identical. But because of Young Canada Works, I get paid. Not for a second do I take this for granted.

So for me, it worked out extremely well. However, given the cuts the Canadian government has recently made to both libraries and youth services, I cannot expect that this solution will benefit a wide range of library students. If anything, the number of beneficiaries is only likely to decline over the next few years. I understand why many feel that unpaid internships are their only option.

The thing is, I should not be too swift to condemn practicums, as they can be hugely beneficial. Especially since I do still hope to do one. But the circumstances in which students undertake them makes an enormous difference. In my case, McGill offers a winter practicum as well, when students do their ten hours a week in lieu of a fourth library school course. To me, this is key. I will still pay the same amount of tuition. The time I spend doing practicum work will be the same amount of time I would spend on coursework for a fourth class. It will not cut into my summer earning time, nor even the part-time job I hold during the school year. In situations where internships do not negatively impact a student’s financial position, I am all for them.

Have any of you had experience with practicums or internships, paid or unpaid? What effect have they had on your library career? Feel free to share your thoughts with me in the comments or you can tweet me at laurainthelib.