How Do I Work in Rare Books? A Career Primer

By Caitlin Bailey

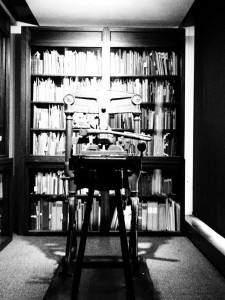

For you Name of the Rose lovers out there, remember Eco’s descriptions of the abbey library and all its mysterious contents? I certainly do; in some way it was responsible for my desire to work as a Special Collections librarian. However, there is a big difference between “wanting and doing” as they say, and pinning down just how to do it has proved problematic. So, to help both myself and others who may be considering the academic and Special Collection stream (either librarians or archivists) I decided to contact the Rare Books department here at McGill and ask, who else? A librarian…

Ann Marie Holland, the Liaison Librarian for the William Colgate History of Printing Collection, the Lande Canadiana Collection and various French Enlightenment collections (among others), kindly agreed to meet me on the fourth floor and to let me ask her all of the annoying unanswered questions that had been plaguing my career path for the last year. During the course of our interview, Ms. Holland revealed herself to be not only charming, but also passionately interested in her field and committed to her work. As she told me the rare books field is not an easily entered career, but once there most people don’t think of leaving.

Ms. Holland received her Bachelor of Arts in French Language and Literature from McMaster University and, after travelling in France for some time, decided to begin the MLIS program here at McGill. She holds a further Master of Arts in French Literature in addition to her MLIS. When asked to speak to the necessity of a second higher-level degree in a relevant subject area, she noted that in the world of academic librarianship it is critical to a competitive CV, though it is possible to work without one.

Regarding the absolute necessity of further schooling, the Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts and Cultural Heritage wrote that 82% of job postings in the field “preferred” a second specialized advanced degree; however, only 14.5% “preferred” a PhD and even fewer required it[1]. However, Ms. Holland noted that for those pursuing a high level position, such as Head or Assistant Head, a PhD might become more important.

When speaking of the research requirements of academic librarians, Ms. Holland was quick to confirm that tenured academic librarians are required to conduct some sort of interest-based research, which may be based on the physical collection that they administer or alternately how users relate to that collection or libraries in general. While the options for research are virtually limitless, it is still considered “part of the job”; Ms. Holland has published book reviews for Papers, the journal of the Bibliographical Society of Canada and has written several articles highlighting the collections at McGill.

Perhaps the most critical question for those of us looking for an entrance into what is acknowledged as an extremely tight field is “how do I start?”. Ms. Holland pointed out that while your first academic job may not be in a special collection per se, some experience with rare materials is essential. In her own case, her entry came after working in the architectural collection (which included a small archival holding) at the Université de Montréal. Furthermore, Ms. Holland noted that volunteering work is a good way to gain initial experience and may garner later contractual work.

As many of the positions in Special Collections are rarely advertised and often occur through word of mouth, it may be difficult to find a permanent position immediately. Ms. Holland originally arrived at McGill as a replacement librarian and later left to work for an antiquarian book dealer in Montréal, when the official funds for her position ran out. Those with experience in the commercial antiquarian book trade may find themselves with an even more competitive CV. Again, the prerequisites for the Fisher position state that experience in ‘’the trade’’ is also preferred.

When asked about the future of Special Collections, Ms. Holland replied emphatically that it is digital, something which even the notoriously closed Vatican Library is embracing in its joint project with the Bodelian Library at Oxford. Special collections are notoriously difficult to physically access; as such digitization provides a particularly neat solution, given that most rare materials are not held under copyright laws. Through the increased use of digital exhibition techniques, Ms. Holland explained that collections were becoming available to a completely new audience and furthermore that audience is extremely excited to have the opportunity to “see inside” these famous treasure troves.

Perhaps the message we seekers of Special Collections careers should take from Ms. Holland’s thoughts is that while the path may be difficult, good things await those who persevere. Like many library jobs, the key appears to be experience, patience and the ability to learn from every job you take. Then one day you too may be involved digitizing a 10 ft.-long set of life-sized architectural specifications (drawn by hand) by the early 20th century architect Percy Nobbs, as Ms. Holland is currently doing for a future exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada.

Sources Cited:

[1] Hansen, K. (2011). “Education, Training, and Recruitment of Special Collections Librarians: An Analysis of Job Advertisements.” RBM: The Journal of Rare Books, Manuscripts, & Cultural Heritage, (12)2, 110-132.